The Hidden Physics of Falling as Experienced By Your Body

Quick Overview: Part 2 in a series on how a fall affects movement

This is the second in a series exploring how a fall can quietly affect your ability to move. In this series, we’re diving into what most recovery models completely miss:

- How falling creates hidden disruptions in your movement system (Link to part 1.)

- The physics of impact — and how your body absorbs force

- Why a fall in childhood has unique implications

- Ways to help yourself, given the specific nuances from your fall

Welcome! I take an engineering-based look at how muscles work together as a system for movement and coordination. You have pain or balance concerns when they don’t, and it turns out there is usually a trauma, illness, or developmental glitch at the root. It’s the kind of thing your doctor likely didn’t study — but it explains a lot about what you’re experiencing.

Welcome! I take an engineering-based look at how muscles work together as a system for movement and coordination. You have pain or balance concerns when they don’t, and it turns out there is usually a trauma, illness, or developmental glitch at the root. It’s the kind of thing your doctor likely didn’t study — but it explains a lot about what you’re experiencing.

Falling … and Why It Sometimes Stays With You

Falling, whether it’s a slip, a trip, or being knocked over, often leaves us rattled. Most of the time we bounce back. But not always.

We often treat falls as isolated events: you fall, you heal, you move on. But the body doesn’t experience impact in isolated parts — it absorbs force as a system. Physics is the science that explains this.

When the physics of our system are disrupted, the body compensates. Those compensations may allow you to keep functioning. But they also lead to lingering stiffness, disrupted breathing, balance issues, or the sense that your body just doesn’t move the way it used to.

Most rehabilitation models don’t account for how forces affect us after impact. This gap leaves many people doing “all the right things” without real resolution.

Let’s look at what normally happens in our body, and then what commonly happens when we fall.

How Force Normally Flows From the Ground Up

Let’s first look at how force is supposed to move through the body. Once you see how force normally flows, it becomes much easier to understand why a fall can leave your body off-kilter long after the bruises fade.

Let’s first look at how force is supposed to move through the body. Once you see how force normally flows, it becomes much easier to understand why a fall can leave your body off-kilter long after the bruises fade.

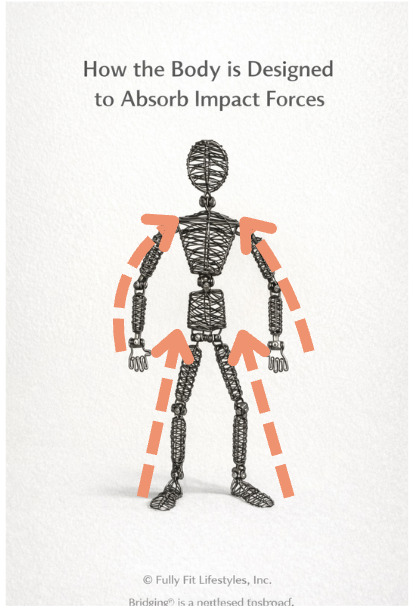

When your feet strike the ground, the chain reaction of movements both propels you forward and absorbs force at the same time. This phenomenon is called a ground reaction force. The way the structure of the body dissipates this force through the feet and legs is such an elegant design. (Reference the image.)

Here are the key stages of how ground reaction forces move through the body:

Foot – Pronation

When the foot strikes the ground, the mid-foot bones and muscles (the metatarsals that form the arch) roll toward the big-toe side. The arch flattens slightly—this is called pronation. Despite what some shoe and orthotic marketing suggests, pronation is essential. This rotational movement initiates force absorption and sets off a coordinated chain reaction up the leg.

Ankle

The many bones of the ankle allow foot pronation to connect to rotational movement of the tibia (shin bone). The ankle also links flexion and extension of the foot to the calf and shin muscles. When this relationship is disrupted, people often experience shin splints or chronically tight calves.

Lower Leg (Tibia, Fibula, and Muscles)

The lower leg contains two bones:

- The fibula, which provides stability

- The tibia, which rotates

The tibia’s rotation absorbs force in a piston-like manner, slowing and distributing load before it reaches the knee. This torsional force absorption is one of the knee’s main protectors.

The Knee

Though surprising to many people, the knee is not a primary force absorber. Instead, when the knee is straight — or mostly straight — it serves as a connector, transmitting force from the lower leg to the upper leg. Knee injuries most often occur when the knee is bent and twisting — conditions it was never designed to manage under load.

Thigh (Femur, Hamstrings, Quadriceps)

The upper leg is a powerhouse for both movement and force absorption. The hip joint allows for strength and mobility, while ground forces stress the femur in ways that support bone density. The large thigh muscles benefit from this stress — they are doing exactly what they were designed to do.

Abdomen and Pelvis

The pelvis, gluteal muscles, and deep abdominals are major force generators and absorbers—especially during side-to-side and rotational movements. The pelvis “winds up” to absorb force and then releases it, creating the natural swagger of walking and running.

The Upper Body Mirrors the Lower Body

The upper body has a similar architecture, with force flowing inward toward the core. Our hands, arms, and shoulders dissipate force when we are pushing or catching.

Both arms and legs develop these force-handling systems in infancy through tummy time, rolling, crawling, squatting, and kneeling.

All that time on the floor pays dividends for life!

Three Ways Force From Falling Goes Off Track

When we fall, force usually enters the body in ways it was never designed to manage. Three main issues tend to create movement blocks that don’t resolve on their own:

1. Speed Creates a Jam

An ultra-fast force can strike so quickly that normal force-distribution mechanisms don’t have time to engage. The force becomes concentrated — and normal movement gets stuck.

2. Magnitude Creates a Jam

Falls often begin with a small loss of balance we can’t recover from. By the time we hit the ground, gravity, body weight, and speed combine into a large force. The greater the magnitude, the more likely structural alignment shifts — disrupting how the musculoskeletal system functions.

3. Torque Creates a Lock

Twisting while falling is a natural protective response (martial artists call this “rolling into it”). But twisting combined with impact can leave the body locked—much like a protective twist-top container.

(4. Children’s Unique Considerations: Falling becomes even more complex with children because development is still underway. That’s what we’ll look at next in the series.)

Physics of Two Common Types of Falls

Falling backwards and falling to the side are two of the most common ways we fall. The visuals should help you understand why they can be particularly vexing to recover from.

The lines of force hit the body in a way that it was not designed to handle!

Falling Backward

Falling Backward

(Slip on ice or water)

In this scenario, force is driven directly into the pelvis, ribcage, and shoulder girdle — areas not designed for primary impact absorption. Structures tend to freeze or jam. What you may experience:

- Limited rotation

- Shallow breathing

- Difficulty sleeping

- An inability to sit comfortably, constantly shifting trying to find relief.

Falling With a Twist

Falling With a Twist

(Falling forward while trying to catch yourself)

These impacts are varied, often in multiple parts of the body, and in multiple directions as noted in the diagram.

Forces include torque, compression, and shearing (one part moving while the other stops much like two parts sliding opposite of each other) all at once. Each creates unique disrupts to joint function and movement flows in the body.

What you may experience:

- Exercises help one area but aggravate another.

- Sleep, focus, and movement feel off.

- Imaging looks “clear,” and your Orthopedist, Physical Therapist, or Chiropractor says you’re fine — yet you don’t feel fine.

The Good News

Ready to Start Resetting the Effects of a Fall?

Bridging sessions focus on clearing the jammed and/or twisted muscle relationships that falls often leave behind.

Most people notice meaningful change after the first session. One or two follow-ups help fully restore coordination and reaction timing.