Respiratory Illness: What You Can Do to Help Yourself and a Recap of the Series

Quick Overview: Part 4 in a series on how respiratory illness affects movement

This is the fourth, and final, article in a series exploring how respiratory illness can quietly affect your ability to move, even years later. In this discussion, I’ll summarize:

- How breathing relates to restrictions in the rest of the body

- Why a respiratory illness in a child can also impact development

- The basic physics that explain how breathing and movement are linked

- Ways to get some relief when Bridging is not an option for you

Breathing and Body Structure

I take a fresh look at assumptions about how muscles work together as a system. When muscles don’t work well together, I look to the past to identify trauma, illness, or development that might be the cause. It’s the kind of thing your doctor likely didn’t study — but it explains a lot about what you’re experiencing.

Time and again, I’m surprised to find that the only unusual event in a client’s history with ongoing movement challenges is an extreme respiratory illness years earlier.

What remains isn’t the illness — it’s residual chest tightness that acts like an anchor, restricting how movement should flow through the body. In this note, I’ll review and share some suggestions for how to get help when coming in for Bridging is not an easy option.

The next discussion series is particularly relevant for those of you who may have fallen with recent ice and snow — we will explore why your recovery may be stalled after falling.

🌬️ Series Wrap-Up on Respiratory Illness Impacting Movement

Respiratory illness can leave lasting effects on how your body moves, breathes, and produces energy — even long after you’re “better.”

If you or family member still notice:

- fatigue that doesn’t make sense

- tight shoulders, hips, or chest

- posture changes

- breath that never feels satisfying or full

…it may not be a fitness issue. It may be a breathing mechanics issue.

The good news: these patterns can change.

👉 If you want the most direct and precise reset, schedule a Bridging session (in person or virtual).

👉 If that’s not possible right now, try the supportive strategies below and notice how your body responds.

Better breathing isn’t just about air. It’s about restoring the pressure system that supports the way your entire body moves.

🛠️ What You Can Do to Help Yourself

How can you support your breathing–movement system after illness?

How can you support your breathing–movement system after illness?

Ideally, you would receive an in-person or virtual Bridging session to help reset the muscles involved in breathing. I realize that’s not always practical, so here are ways to apply the same pressure principles at home.

They may not be as precise as Bridging, but they can help move things in the right direction. The key is pressure relationships — not “taking deeper breaths.” Think of this as a gentler, more subtle version of the Heimlich Maneuver concept: changing pressure so the system can reorganize itself.

To help breathing reset here are three options. You can try any one, or all! (The video link below will help you visualize the first reset option.)

1️⃣ Light external compression of the chest (with help from a friend or partner)

Gently match the pressure of the outer chest wall to the pressure inside the chest. This can help the rib muscles relax and allow more natural expansion to return.

How: While sitting or lying on your side, have a friend place their hands, a folded towel, or a soft cushion against the back and front side of the lower ribs while breathing normally. The pressure should be light and supportive — never forceful. If you can imagine holding a big sandwich together, that will be about right! Hold the position for 30-60 seconds and you will notice the breathing muscles beginning to relax.

2️⃣ Support the ribcage–diaphragm border (done by yourself)

Helping the border area between the lower ribs and the diaphragm muscle relax which often allows the diaphragm to resume its natural up-and-down rhythm.

How: While lying on your stomach, place soft, steady support (hands, pillow, or towel) at the lower edge of the ribcage. Stay relaxed and allow breathing to happen rather than trying to control it.

3️⃣ Use gentle breathing resistance

Some devices create mild resistance to inhalation, which can help rebalance pressure relationships from the inside, rather than an external approach.

Example: Devices such as PowerBreathe or the Breather have research supporting their use for respiratory muscle training and pressure regulation. This is not the same as the Incentive Spirometer device used after surgery to improve lung inflation.

🚫 What I’m not suggesting for the breathing reset

The above options are not the same as meditative breath work, box breathing, or deep breathing drills. While helpful for relaxation or lung expansion, they don’t directly address the pressure system imbalance that illness can leave behind.

Example of Bridging® Style Support

In this short video I talk you through what you’ll typically find after a respiratory illness. You will also see how I provide light support to the chest, which allows the muscles to reset and expand further with each breath.

Although this is not the same as an in-person session, you should be able to breathe more easily and relax the shoulders and hips more than previously.

Recap: Basic Respiration Movement Impacts to Other Movement

In case you missed parts of this series, here is a quick review about why respiratory illness can create significant challenges to the way your body moves:

1: Structural Interconnections

1: Structural Interconnections

How breathing mechanics affect the rest of the body:

How breathing mechanics affect the rest of the body:

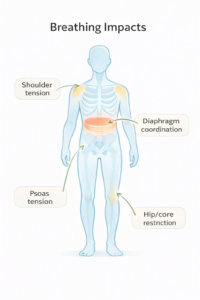

The ribcage is a movement connector, not just a lung container. When the ribs stop expanding well after illness, they stiffen the spine, limit shoulder motion, and restrict how the core rotates and stabilizes.

The diaphragm connects breathing to posture and hips. The diaphragm shares attachment relationships with deep core and hip muscles (especially psoas). When breathing becomes tight or shallow, hips tighten and posture shifts forward.

Breathing restrictions create full-body compensation. If the chest can’t move well, the body finds another way to breathe — lifting shoulders, arching the low back, tightening the neck. These workarounds lead to pain, fatigue, and poor coordination.

👶 2: Developmental Implications

Why respiratory illness in kids affects more than lungs:

Why respiratory illness in kids affects more than lungs:

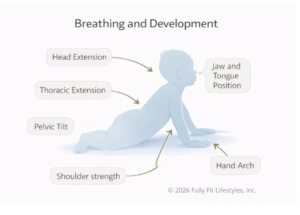

Early breathing patterns shape movement foundations. Babies and young children are building posture, strength, and coordination at the same time they’re growing. Illness during this window can alter how the ribcage, diaphragm, and core develop together.

Oxygen and movement drive endurance and regulation. If breathing is inefficient, kids fatigue faster, avoid physical activity, and may struggle with calming, focus, and emotional regulation — not behavioral problems, but physiological ones.

Shoulder, jaw, and arm coordination can lag. When ribcage and diaphragm movement is limited, the shoulders don’t get a stable base. This can affect arm coordination, upper-body strength, handwriting, and even speech support.

⚙️ 3: The Physics of Breathing

Why “recovered” isn’t always “back to normal”:

Why “recovered” isn’t always “back to normal”:

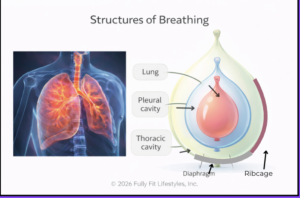

Breathing works on tiny pressure differences. Air moves because of very small pressure changes created by rib and diaphragm motion. If chest expansion is reduced even a little, oxygen intake drops and fatigue rises.

Structure controls pressure — and pressure controls movement. The ribcage, diaphragm, and surrounding muscles form a pressure system. When illness stiffens these structures, the system can’t regulate efficiently, affecting posture, stability, and energy.

Resetting movement restores the pressure system. When rib and diaphragm motion return, pressure differences normalize automatically. Better breathing leads to better posture, easier movement, and improved endurance — without “breathing exercises.”