Respiratory Illness: The Physics of Breathing Explain So Much!

Quick Overview: Part 3 in a series on how respiratory illness affects movement — sometimes for years

This is the third article in a series exploring how respiratory illness can quietly affect your ability to move, even years later. In this discussion, I’ll cover:

- How breathing relates to the rest of the body

- Why “recovered” is not the same as back to normal

- The basic physics that explain how breathing and movement are linked

Breathing and Body Structure

I take a fresh look at assumptions about how muscles work together as a system. When they don’t work well together, I look to the past to identify trauma, illness, or development that might be the cause. It’s the kind of thing your doctor likely didn’t study — but it explains a lot.

Time and again, I’m surprised to find that the only unusual event in a client’s history with ongoing movement challenges is an extreme respiratory illness years earlier.

What remains isn’t obvious illness — it’s residual chest tightness that acts like an anchor, restricting how movement should flow through the body.

My background is in systems engineering, layered with personal training and movement education. The engineering lens is my go-to when thinking about movement challenges — which often means I end up sketching physics relationships to help explain it to you. Fortunately I have ChatGPT help to make it more presentable. I hope you find this helpful!

Louise: Recovered, but Not Back to Normal

We begin with a story….

Louise has been helping me create videos for two YouTube series—one on how movement should flow through the body, and another on how medical procedures disrupt movement.

Good for me … bad for her — she picked up a respiratory bug recently and we were able to make another video about helping her recover. (See the next section.)

When respiratory illness hits Louise, it hits hard. She has a long history of lung issues, and after an illness she often develops lower-body tightness and pain. This related hip tightness is one of the relationships I covered in the first part of this series.

The relationship of breathing and muscle tightness makes more sense when you see it in the video.

In the video, we look at how easily Louise’s core transitions in the three directions (planes) our bodies must move. Spoiler alert: her core doesn’t move.

Next, I break it down more fundamentally to see what’s moving — and what’s rigid. Her upper and lower body don’t move and they should.

Lastly, with Bridging support you will see how her chest, shoulder and hip are moving more easily again.

Yes, it was that quick! The second video link is her reaction once we were all done. She felt SO much better.

Basic Respiration Movement Connections to Other Movement

There are two basic things most health and exercise professionals forget to pay attention to when their clients have restricted or painful movement. These fundamentals are often at the root of pain, limited range of motion, and fatigue:

- Ribcage movement: Does the ribcage actually expand and contract with each breath?

- Diaphragm function: Is the diaphragm moving up and down within the core to regulate breathing?

If the answer to either question is no, the ripple effect throughout the body will restrict movement in multiple places. (And by the way—there is still no standard imaging or ultrasound available to assess diaphragm function.)

You’ll see the Bridging® reset process in the video. How was I able to restore her breathing movement so quickly?

The answer lies in physics.

The Physics of Breathing (Without the Math)

Here’s where things get interesting. A few simple principles help:

1. The body is a vessel

Your bones and muscles form a flexible container. That container must expand and contract for breathing and for posture changes like bending, twisting, and reaching.

2. Breathing REQUIRES pressure differences

Air moves ONLY if there’s a pressure difference between the inside and outside of the body, just like in HVAC systems. No pressure difference, no airflow. To move air for breathing, a very small pressure change is required — about ±1 mmHg.

In the next section, we get into more details about how our bodies regulates pressure change.

Why This System Is Brilliant — and Vulnerable

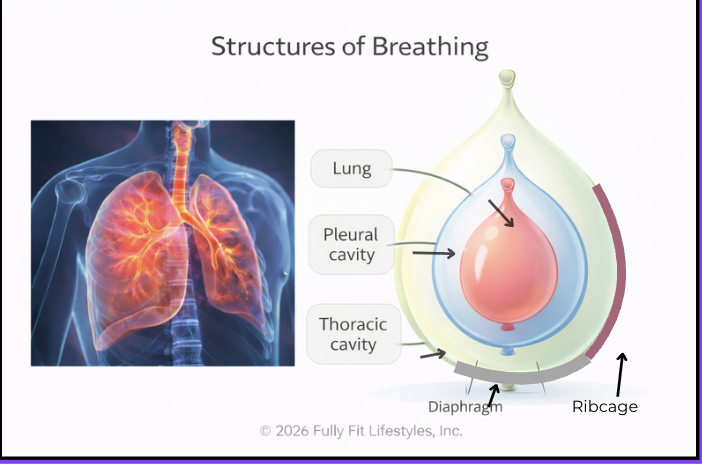

Leaving equations and numbers aside, I want to walk you through the above diagram to show how breathing and movement are inseparable.

Note that breathing relies on multiple nested pressure layers working together:

- Balloon 1 – The chest wall: The Thoracic cavity is formed by the ribs and chest muscles. This structure forms the boundary to the environmental pressure so the chest doesn’t collapse.

- Balloon 2 – The pleural space: An elastic zone between lung and the chest wall, like a balloon inside a balloon, it provides space for the lung to expand.

- Balloon 3 – The lungs: Expands and contracts within the pleural space.

- The diaphragm – A dome-shaped muscle acting like a trampoline at the bottom of the ribcage, creating pressure differences that draw air in and out. It functions similar to a syringe.

We breathe roughly 20 times per minute. The system must be automatic and effortless, and this nested pressure-based system is incredibly efficient and self-sustaining!

From a physics standpoint, pressure systems are incredibly adaptable. Small changes in pressure ripple through instantly to keep the system stable. But when pressure systems are compromised, they’re hard to reboot without specific support.

Why Illness Disrupts This Pressure Flow So Easily

Pressure depends on volume and temperature — basic physics.

What is pressure dependent on?

Physics gives us two laws related to physics, Charles’ and Boyle’s Laws. You may know the names from your high school chemistry or physics classes. They define how pressure has specific relationships to temperature and volume.

- Temperature: Pressure correlates with temperature. Higher temperature causes higher pressure. Think InstantPot cooking for heat and high pressure, and flat tires as an example for cold effects. This is why a high fever is such a concern; it limits breathing.

- Volume: As volume changes, the pressure changes oppositely. If you shrink the volume, the pressure increases.

These laws explain more about why respiratory illnesses may leave you short of breath or prone to tire quickly afterward. The volume of chest expansion is limited due to constricted ribcage movement. Reduced volume means a smaller differential pressure and a smaller intake of oxygen with each breath.

Your body adapts to survive — but that adaptation often becomes your new normal. It doesn’t have to be, though. Your breathing, movement and fatigue can all improve with a Bridging® reset!

Why Bridging Resets Breathing So Quickly

In the video with Louise, her breathing expands within seconds once support is added. Let’s walk this through using the physics principles:

- Illness restricts ribcage movement. The ribcage didn’t move, thus creating a reduced volume for pressure, reducing oxygen intake.

- External support changes pressure, allowing breathing system reboot. Supporting the ribcage changes the pressure of the external environment to match the internal pressure, allowing the muscles to relax, which creates space to begin moving again.

- Pressure regulation resumes. Once the muscles of the ribcage can move, the expansion of the diaphragm is able to regulate deeper breaths.

- Oxygenation improves. The deeper diaphragm movement creates a larger pressure differential for increased oxygen intake.

- Self-reinforcing change. The change to the chest and breathing is self-sustaining because of the pressure relationships. You don’t need to practice breathing!

This is why Bridging changes often feel magical — more energy, less shoulder or hip tightness — but they’re actually mechanical and predictable.

This is physics, not pharmaceuticals.

If you’ve had a respiratory illness, chances are your breathing will benefit from a reset!